|

|

|||||||

|

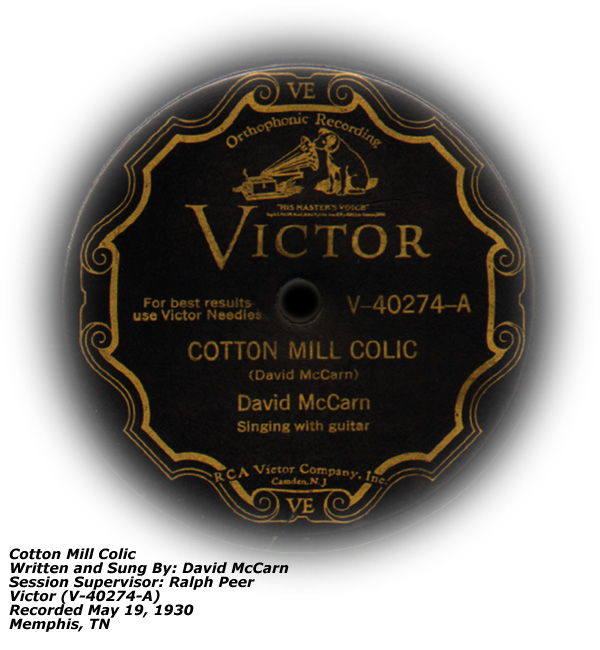

About The Artist John David McCarn was a Carolina cotton mill worker who composed songs about work in the textile industry and a variety of other material. Although usually considered protest songs today, most were cast with a degree of sarcastic humor. William Henry Koon delved a bit into Dave McCarn's life in an essay for the JEMF Quarterly in the Winter 1975 issue. Research into Dave's family show that his father Levi was working in the mills as early as the 1900 U. S. Census. He married Sallie Cousins on January 31, 1904 in Gaston, NC. A daughter was born in April 1901 (Fannie Ruth). Dave was second oldest, born in 1905. Levi McCarn, born on January 6, 1865, died at the age of 54 on June 7, 1919. His mother married James T. Harrison on January 31, 1920 in Mecklenburg, NC. However, she passed away on July 31, 1920. Apparently cause of death is unknown as the copy of the death certificate found listed only "no physician report." When Dave was a small child, his father was working as a farmer. But later, he began work at the Chronical Mill in Belmont. By the time Dave was 12, he began working with his dad at the mill. He took to the guitar in his teen years, teaching himself. He also tried to listen to others so he could learn a better style and improve himself. Koon writes that he began playing with a country dance band called the Yellow Jackets Band and had been heard over radio station WBRW in Gastonia. Dave was probably the only person in the family interested in music. A native of McAdensville, North Carolina, McCarn was the second in a family of eight children and soon moved with his kin to the larger mill town of Belmont and went to work as a doffer in the mill at age twelve, with but little education. Koon writes that McCarn worked in the mills around Gastonia most of the 1920's. But by the 1930's, he started wandering and actually hitchhiked his way to Los Angeles, California. Still on the road in 1930 apparently but Koon indicates it may have been a good place to be. The mills in the area were undergoing labor strife and locations were experiencing strikes. McCarn was said to have joined a union, but was not impressed. However just before his recording debut, Gastonia was in the headlines - a strike at Loray, the deaths of Police Chief Aderholt and unionist Ella May Wiggins. McCarn told Koons about that part of time and working in Gastonia's cotton mills: "Well if you were lucky enough to have a job, you didn't make too much, very much, and well in other words, the wages didn't compare with the prices of food. Food was always higher than the, you know, the wages. In other words, if Cotton Mill announced or that they meant to raise a few cents, groceries would automatically go up way before the raise come. So if they was no point in a raising. It didn't help any. The wages probably made it a little worse. The two recordings that McCarn made in Memphis happened by pure happenstance or luck. He was traveling with his younger brother, perhaps looking for work. They were in Memphis and it appears they were at the end of their ropes financially. Koons let McCarn tell of how that stay in Memphis went but also noted that his sister Mrs. Nellie Sansing told a Charlotte newspaper in 1969. He tells of meeting Ralph Peer and even Jimmie Davis. Koons quoted McCarn: "... we happen to wind up in Memphis, Tennessee, one time, and we got down a little bit, you might say, broke. And I had a little old guitar, a little old Stuart. It had a nice soft tone to it and we was a making the hock shops , try to hock it you know for a few bucks. But three bucks was the only thing we got offered and I wouldn't take that so the last hock shop we stopped in, there was a couple of boys in wanting to get strings for the instruments there. And, the proprietor, the, the proprietor or the manager says, asked the boys if they was going to make a record. Yes, if they could get some strings to stay on these instruments. I believe one had a tenor banjo or anyway he had it high strung. While his sister Nellie told a different account of his recording efforts, Mrs. Sansing also told of Dave's early life and experiences. She told Claudia Howe who wrote the article that the hard times shaped her brother's life. She said, "Dave was different from the rest of us. There ws eight of us young'uns and papa worked in a mill at McAdenville and never brought home more than $6 a week in his whole life." (Note: A search was made of the internet to see what $6.00 in 1918 would be worth in 2022 - just over $114 was the result.) Their father died in 1918 and Dave was only 13 at the time. She tells of her father's life and his death's impact on Dave. "Dave was only 13 when papa died in 1918. Papa had the flu the year before and it ruint his lungs. He'd always worked in the mill and raised chickens, hogs, kept a cow and raised a garden to feed us all. It is perhaps fortunate the newspaper columnist got to talk with Nellie, Dave's sister. She passed away a few weeks later on Saturday, September 21, 1969.

Below is a verse from the tune: Mr. Koons got Dave to explain why he called that tune "Cotton Mill Colic." (Note: The use of the word "colic" is another way of saying "crying about" or "complaining" as used in this song.) " Well, oh around the town a lot of people say they have the colic when they are griping about something, and they will say let's attack about, let's colic about it and go do something else. Well I just uh, put it down "Cotton Mill Colic" because I was colicing about the times in cotton mills and things, I guess, it seemed to be the perfect word for the song . . . but a lot back then did use it but I don't hear it too well sometime you might hear it. Yes, but not as often as you used to, but another words it's just a word. Just some saying the heck with it or your not treating me right or something. "

McCarn's sister said he never got much money from the records he made, just a bit from royalties. But Claudia Howe closed her piece on the hard times of a mill hand: "...But McCarn was more than a singer of songs. He was a spinner of dreams, a safety valve for all the pent-up emotions of a time and a place where men groped through the darkness. Credits & Sources

Sound Sample—(YouTube Video Format)

|

| Printer Friendly Version |

|

Recordings (78rpm/45rpm)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hillbilly-Music.com

Yes, Hillbilly Music. You may perhaps wonder why. You may even snicker. But trust us, soon your feet will start tappin' and before you know it, you'll be comin' back for more...Hillbilly Music.

Hillbilly-music.com ...

It's about the people, the music, the history.

|

Copyright © 2000—2023 Hillbilly-Music.com

|

||||